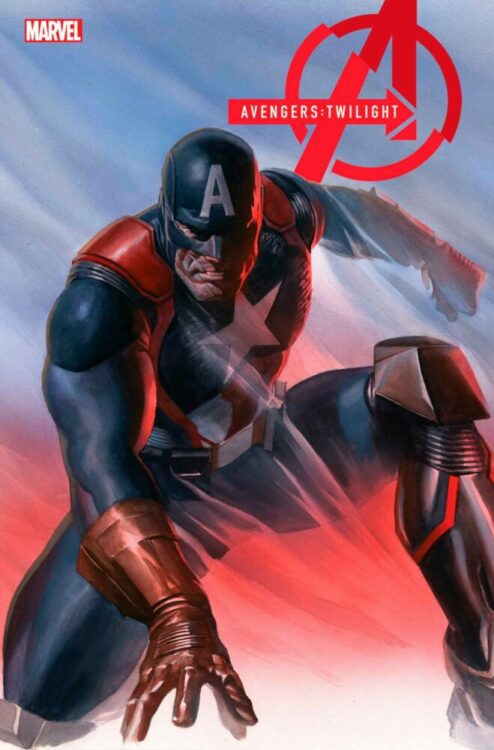

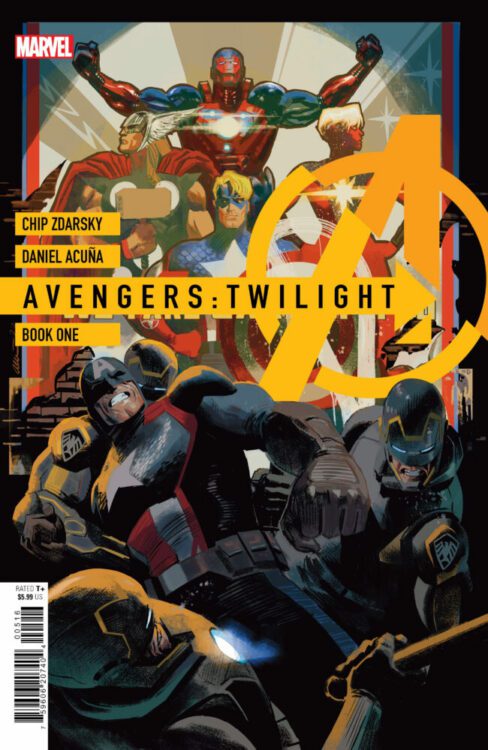

Three pages into Marvel Comics’ Avengers: Twilight #1, you’ll realize something: You’re watching comic book history as it’s being made. Writer Chip Zdarsky, artist Daniel Acuña, and letterer Cory Petit pull us into the tired, old future of the Marvel Universe. Something about it all feels startlingly real. While we get glimpses of things we’re familiar with, Avengers: Twilight‘s stomping ground is almost entirely new. Zdarsky, Acuña, and Petit are boldly original in their worldbuilding, and beautifully understated in their storytelling. They’ve created an unassuming masterpiece that is sure to be an instant classic.

Writing

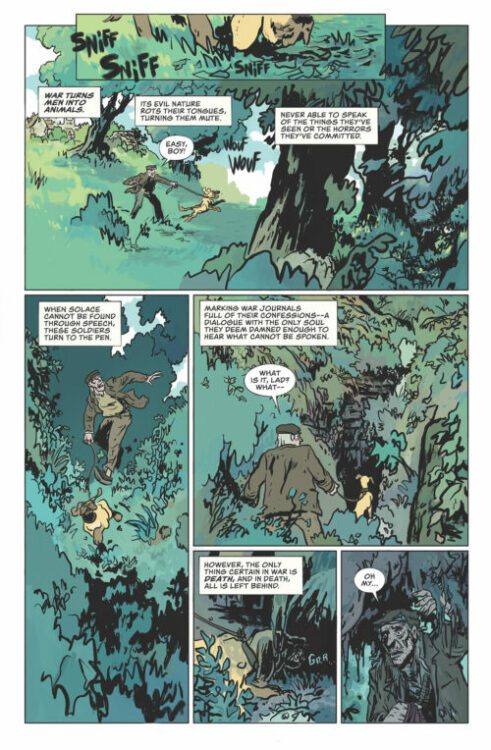

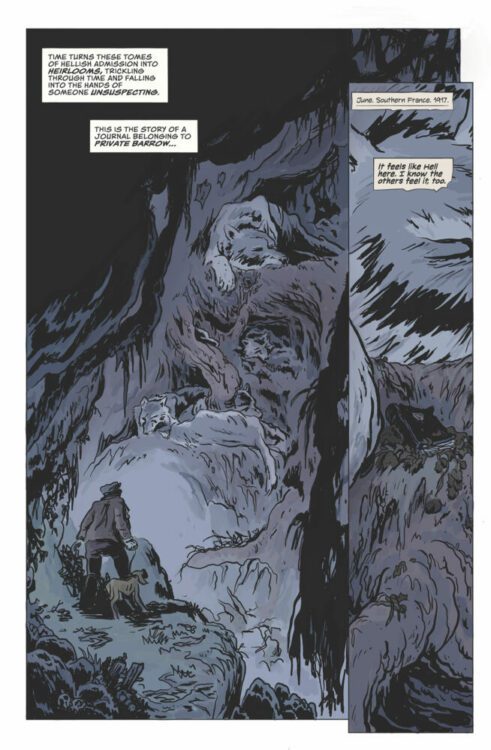

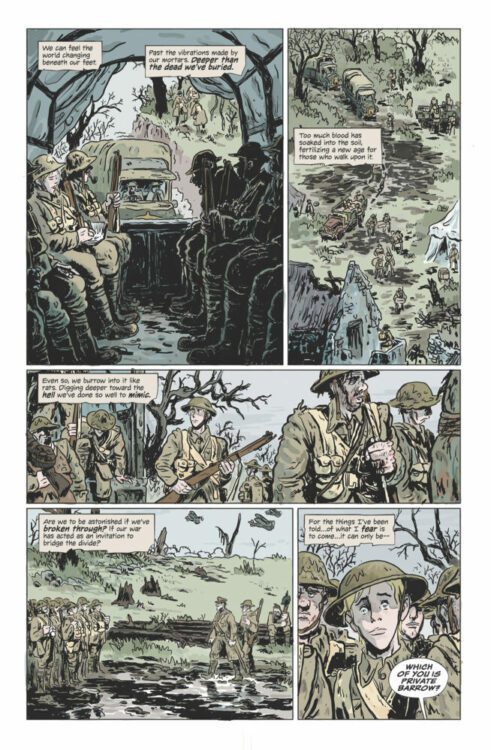

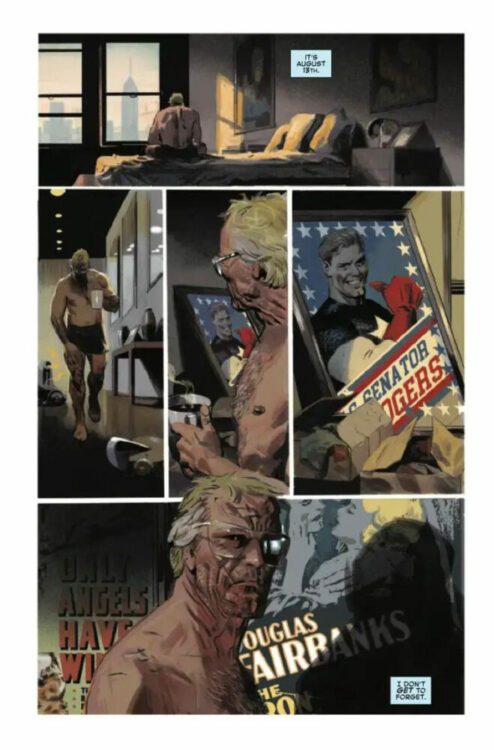

It’s so tempting to go into the details of what makes this story so compelling. Zdarsky’s use of the Marvel mythos is masterful yet restrained. But to talk about these things would be to rob readers of the quiet realizations and connections that pop up in these pages. What I can say, is that Zdarsky’s sense of rhythm here is unparalleled. As we follow an old, retired Steve Rogers, he takes on life with gusto and energy. The panels are filled with caption boxes and word balloons, showing how much he’s trying to engage with an environment that mostly seems to have left him behind. But when he’s hit with a wave of nostalgia, in all its guilt-tinged glory, the panels empty out of thoughts and words. Zdarsky leaves Steve in the heavy silence, free of any welcome distractions.

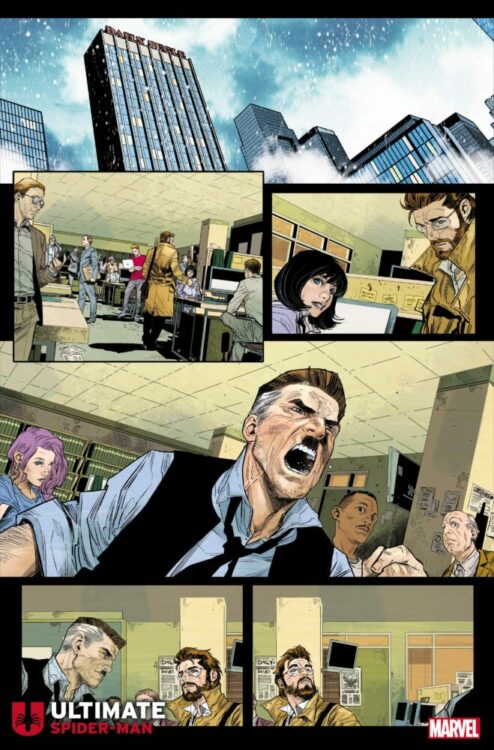

Every character feels like a full-fledged human being. When Steve debates a younger man — who at first seems entirely cruel and self-serving — you want to be on Steve’s side. But the young man’s final words leave you with a lump in your belly and the quiet realization that he actually makes a valid point. And yet Steve also isn’t just an old man who’s refusing to accept that times have changed. He’s trying his darnedest to be a good man in a world that feels more and more foreign to him. His pals who don’t want to move on from the glory days aren’t curmudgeons either. They’re trying desperately to hold onto their morals, and doing their best to stave off bitterness and fear. At one point, enraged by a TV special, Steve says, “Nobody cares about the truth anymore…” As we read on, it becomes clear that Steve is wrong about that. People do still care. They’re just too overwhelmed with information to know what is true anymore. It’s moments like these that we see that Zdarsky’ is writing about more than just superheroes. He’s writing about us.

Artist

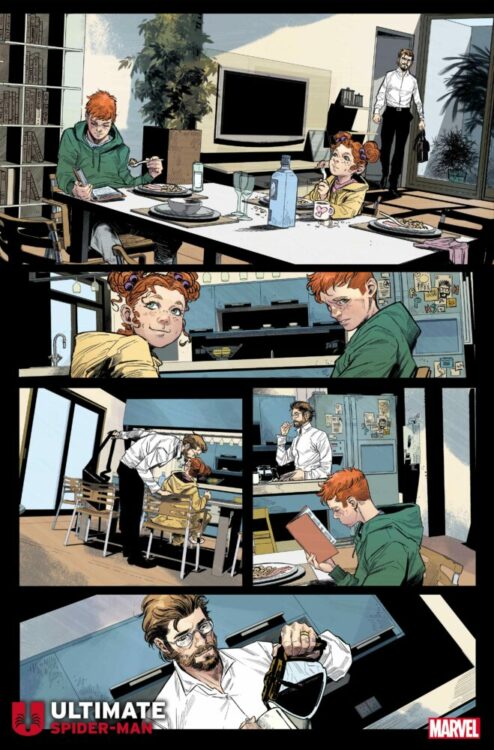

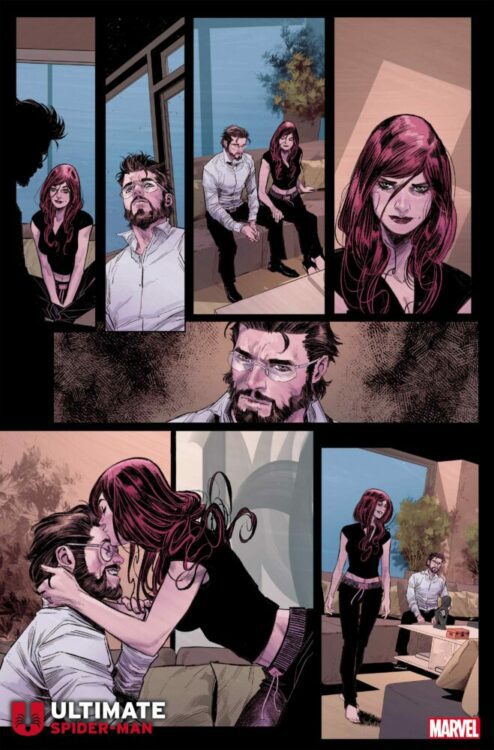

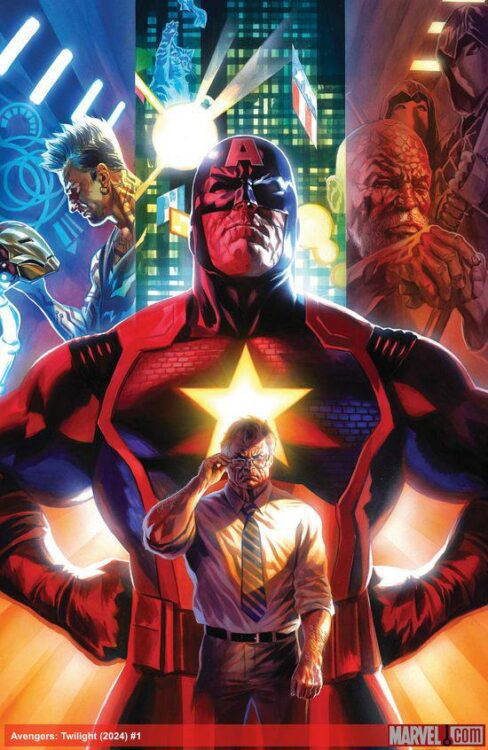

It feels like an incredibly daunting task to talk about Acuña’s art. The painted texture of it, the lighting, the colors, the acting of the characters… it’s all spellbinding. In every panel, Acuña has added to the story with wonderful details and flourishes. Steve Rogers’ world is dull and grey compared to the brightly colored image of his younger self. The brave face he puts on for everyone else seems to be one of tempered rage. His brow is forever bunched up into a knot and his mouth is in a permanent scowl. It’s the defensive wall he puts up, though we occasionally see through some of its cracks. When we do, Steve limps along with a worn out gait and a subtle expression of sad capitulation.

So much of the worldbuilding happens through Acuña’s colors. When Steve walks down the street, he’s surrounded by fluorescent, futuristic billboards that hover about the place. He and his pals choose to meet up in Central Park, bringing us back to a more natural color scheme that is only occasionally interrupted by the garish stain of consumerism. With this simple choice, Acuña tells us volumes about these old souls. Wherever they can, they try to find oases from the luminescent hell that seems to have become mundane to everyone else. At the end of the day, they seem like they just want a break from it all.

Of course, Acuña’s work goes well beyond these few things. His artwork is simply some of the most astonishing work you’ll ever see in comics. It’s moody, stylish, and atmospheric. But it’s also clearly driven by the story itself, expertly drawing out each beat of the script in stunning ways.

Lettering

Petit’s lettering blends into the panels of this comic so seamlessly. As you read, you feel you’re experiencing each scene with the characters, rather than reading about it on a page. There are little moments that stand out as ingenious details that help you to really hear the words. When Steve is in his debate, the young man interrupts him with a word balloon that has smaller a font to it. The quiet, impatient exasperation is immediately obvious. When they next interrupt, any feigned politeness is gone. Their words are just as big as Steve’s as they wrest control of the conversation from him, leading him to yell back in big, bold font. Petit shows us each step of this argument escalating, but in such low-key ways that he doesn’t break your attention away from what’s happening. Petit’s work is subdued and serves the story brilliantly.

Conclusion

This isn’t just a fantastic new comic. This is the next Kingdom Come. It’s Watchmen. It’s The Dark Knight Returns. This is the first issue of a comic that we’ll be talking about for decades to come. It’s the start of a ground-breaking new move in superhero comics, and Marvel won’t be the same when it’s over.

Zdarsky, Acuña, and Petit have taken our modern anxieties and infused them with a mythological grandeur. When you read Avengers: Twilight #1, you’re quite simply reading the next step in the evolution of superhero comics. Avengers: Twilight #1 is out today from Marvel Comics, and you certainly don’t want to miss it!