The origins of modern Manga, like Comics as a whole, are challenging to map out, but its influence on the industry the world over is apparent. Exhibit A: Ghost Cage by Nick Dragotta and Caleb Goellner, published March 23 by Image Comics.

A quick flick through the opening pages reveals two things. First is Dragotta’s distinctive style, and second is the unapologetic manga homage. Everything about this comic is a love letter to the storytelling techniques of master artists such as Osamu Tezuka, Katsuhiro Otomo, and Hiromu Arakawa. Falling into the seinen manga traditions, Ghost Cage is both a spiritual successor to Dragotta and Hickman’s East of West series and an exploration of manga traditions through Western eyes.

(Spoiler Warning: The following may contain mild spoilers for Ghost Cage #1)

Shared Motifs

Throughout the first issue of Ghost Cage, Dragotta plays with the motifs and styles of seinen manga to produce something that will be familiar to his fans but is also clearly drawing influence from elsewhere. Anyone not familiar with Manga will find the expressive visuals excessive, and the general pacing of the narrative may be confusing. However, Dragotta will attract a reader who is well-versed in different comic formats, so this stylization is nothing new. It was impossible, for example, to read any of East of West without engaging with the manga influence.

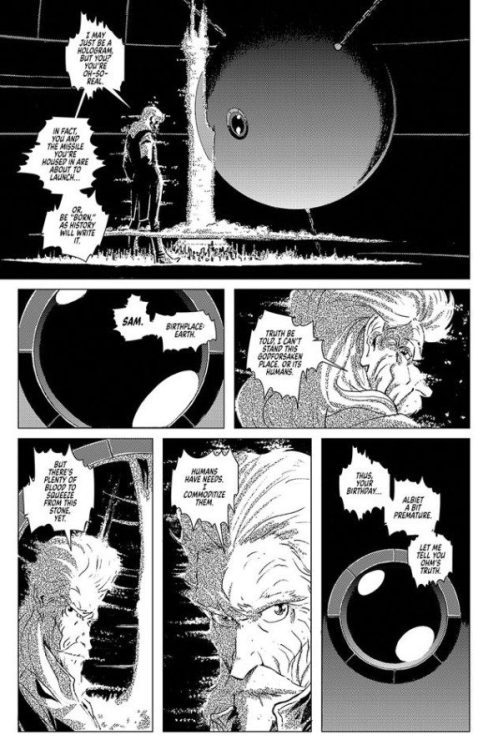

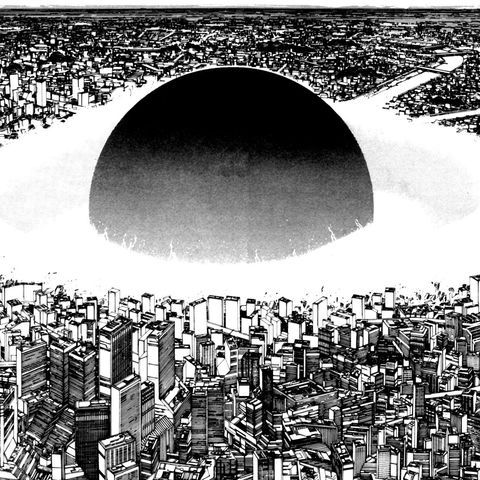

In Ghost Cage, the reader is treated to several seinen motifs that have become synonymous with the young boys’ comics of Japan. The comic has a strong focus on action and conflict from the very beginning. The opening page contains the illusion of a face constructed from a grotesque collage of body parts. This is instantly followed by a cityscape that resembles a massive explosive force reminiscent of the destruction in the pages of Akira from Katsuhiro Otomo. Undoubtedly, this narrative will feature violence as an overwhelming element of its structure, and Dragotta prepares the reader for the oncoming onslaught.

But in true seinen fashion, the violence is just a tool for more profound, more political storytelling. Dragotta creates a ‘them and us’ aspect to the characters with a clear divide between the rich and powerful and the poor and oppressed. This is an awe-inspiring task as there are very few characters in this opening issue. What Draggotta creates, similar to several classic Japanese science fiction stories, is a hierarchical society of location and landscape. The visual representation of society symbolizes human struggles. The opening includes a silhouetted city that is towered over by a single structure of power. This edifice turns out to be the actual source of power for the sprawling city beneath it. The phallic erection in the center of the page represents corporate greed and domination. And everything that follows furthers the ongoing struggle of the working classes against the corrupt, self-obsessed ruling classes. The hero of the story is a tech nerd who spends her time desperately trying to impress her bosses just so that she can advance through a system that uses and abuses her. It’s a story of manipulation that many readers will identify with.

However, there is an overwhelming sense of hope in the narrative. Doyle, the central character, grows in emotional strength and confidence with each conflict. She can change her initial obedience into a survival instinct and then transform herself into an opposing force against the system. The working-class hero or underdog is a major feature of many science fiction manga comics. The conflict between an overpowering corporation and youthful defiance plays well with the seinen target audience, as it does the readers of Image comics. Image Comics, reaching its 30th year in publishing this year, was initially set up by several artists and writers disgruntled with the corporate nature of the two main comics publishers, Marvel and DC. The founders were making a stand against the dominance of those publishers and were fuelled by their youthful exuberance. That defiance is reflected in the pages of Ghost Cage.

Landscaping

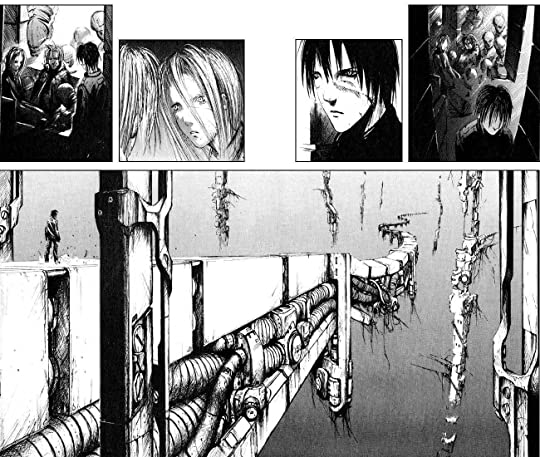

One feature of Manga is the treatment of landscapes. The setting is very important to the narratives, but there is also a disregard for backgrounds. Locations are used to create a setting and give the narrative its grounding or location, but the focus dramatically shifts to the characters when the action starts. Action lines drown out the need for background, and after the initial establishing shots, the readers are expected to place the drama. However, when landscapes are used within Manga, they are superb, complex worlds, often beyond imagining. From the expressive streets of Neo Tokyo in Akira to the machine underworlds of Tsutomu Nihei’s Blame! landscapes are more than settings. They are an integral part of the narrative symbolism.

The accent aspect of Ghost Cage is reminiscent of Blame! Within both comics, the opening paints a dystopian future world of contrasts between light and darkness, of expansive vistas and closed spaces, and of life and death. The setting creates an ever-present threat, and, in both examples, the futuristic landscapes are vast in scale and, somehow, confining and claustrophobic. You never get a feeling of freedom, only oppression, and entrapment. The world is closing in, and the only option is to fight against it and physically rise up from the depths. The single-minded violence, as represented by the fight sequences devoid of backgrounds, is a necessity born from the world in which the characters live but want to escape.

Awe-Inspiring Homage

Dragotta has a fairly distinctive style in his mainstream work, but it is in the independent and creator-owned work where his style really shines. East of West was a powerhouse of storytelling with visuals that are worth returning to again and again. With Ghost Cage, Dragotta has leaped fully into recreating a modern manga-style comic, reflecting some of the most excellent seinen strips from the last 40 plus years. But, again, there is evident respect for the Japanese traditions, and Dragotta enjoys playing in the vast sandbox of manga techniques.

Manga is a massive art form, and there are plenty of books out there if you are interested in the subject. But be warned, it’s not like getting into a different genre; it is more like learning a new language. Ghost Cage interprets that language and adapts it to fit a monthly American comics release. Even before you look at the narrative, the visual onslaught of Dragotta’s work will have you transfixed to this extraordinary comic.