Among the many refrains found in the comment sections of articles and message boards across online comicdom, perhaps none is so popular as “keep politics out of my comics!” This knee-jerk response to creators expressing – or even suggesting – political leanings in their work often brings with it a rosy and ahistorical picture of the past. This is a time before “politics ruined comics” – back when Superman fought only robots, Batman foiled only the Joker, and Wonder Woman’s only war was against Greek gods. Even Captain America is somehow absolved of political leanings, his Nazi punching only begrudgingly considered somewhat political.

This vision is as imaginary as superheroes themselves. Only a cursory look into comics history is necessary to recognize how politics have informed superhero comics again and again and again. Superheroes owe their success in part to the progressive politics of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, whose first Superman story pitted the Man of Steel against explicitly political enemies. In that two-part story (1938’s Action Comics #1 and #2), Superman saves a wrongfully convicted woman from the death penalty, stops domestic violence, investigates a corrupt American senator, and uncovers a plot between a lobbyist and a munitions tycoon to orchestrate a civil war in a Latin American island nation, so that they may reap the profits.

imaginary as superheroes themselves. Only a cursory look into comics history is necessary to recognize how politics have informed superhero comics again and again and again. Superheroes owe their success in part to the progressive politics of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, whose first Superman story pitted the Man of Steel against explicitly political enemies. In that two-part story (1938’s Action Comics #1 and #2), Superman saves a wrongfully convicted woman from the death penalty, stops domestic violence, investigates a corrupt American senator, and uncovers a plot between a lobbyist and a munitions tycoon to orchestrate a civil war in a Latin American island nation, so that they may reap the profits.

The politics didn’t stop with Superman: William Marston referred to his feminist co-creation Wonder Woman as “psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world;” Captain America was a New Deal Democrat whose origin story rebutted the Aryan superhuman myth; Iron Man’s character arc is one of rejection of state power and remorse for having contributed to state violence. And let’s not forget the most explicitly political superhero of them all, Green Arrow, identified at various times as either an anarchist, a Marxist, or a “commie,” and whose defining attributes include his distrust for authority and the rejection of his wealthy inheritance. (One of the reasons why CW’s Arrow never rang true for me was the neutering of Oliver Queen’s politics.)

The politics didn’t stop with Superman: William Marston referred to his feminist co-creation Wonder Woman as “psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world;” Captain America was a New Deal Democrat whose origin story rebutted the Aryan superhuman myth; Iron Man’s character arc is one of rejection of state power and remorse for having contributed to state violence. And let’s not forget the most explicitly political superhero of them all, Green Arrow, identified at various times as either an anarchist, a Marxist, or a “commie,” and whose defining attributes include his distrust for authority and the rejection of his wealthy inheritance. (One of the reasons why CW’s Arrow never rang true for me was the neutering of Oliver Queen’s politics.)

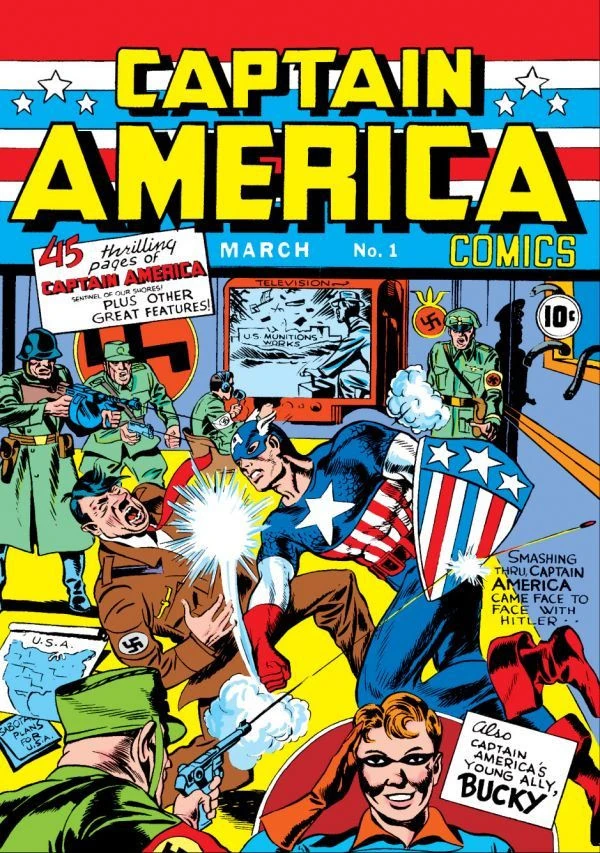

The very covers of comic books have served political purposes. Throughout World War II, comic book covers were used by publishers and creators to encourage patriotic fervor among America’s youth as much as to sell comics. Even before the United States entered the war, Jack Kirby’s iconic cover for Captain America Comics #1 featured Cap punching a foreign head of state – Adolf Hitler. Though well received by most, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s first issue was also met with anti-Semitic hate mail so serious that New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia personally contacted the two creators to promise protection.

The very covers of comic books have served political purposes. Throughout World War II, comic book covers were used by publishers and creators to encourage patriotic fervor among America’s youth as much as to sell comics. Even before the United States entered the war, Jack Kirby’s iconic cover for Captain America Comics #1 featured Cap punching a foreign head of state – Adolf Hitler. Though well received by most, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s first issue was also met with anti-Semitic hate mail so serious that New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia personally contacted the two creators to promise protection.

Superheroes, like all fictional creations, reflect their creators, and American comic book creators tend to be, on the whole, liberal (so liberal, in fact, it has led some conservative creators to complain about not being able to get work). Trump’s ascendence has seen an outpouring of outrage among most creators on social media, along with a reaction against that outrage by both those who don’t share their liberal beliefs and by apolitical comic book fans. The debate over how political comic books (and, by extension, comic book creators and publishers) should be has grown – many even say that they shouldn’t be political at all. But such demands have fallen on deaf ears, and some creators have extended their politics well beyond the comic book panel. Both Humberto Ramos and the legendary George Perez will be boycotting conventions in states which voted for Trump. And, more and more, publishers have not been afraid to wear their politics on their sleeves.

Last December, IDW and DC co-released an anthology entitled Love Is Love, to benefit the victims of the Pulse nightclub mass shooting last summer in Orlando, Florida. Image Comics recently announced that they will publish a special line of variant covers for Women’s History Month in March – 100% of the proceeds of which will be donated to Planned Parenthood. This decision by Image led Florida retailer Phil Boyle of the Coliseum of Comics store chain to write an open letter demanding publishers “get [their] politics out of my stores!” Boyle bemoaned the threat such initiatives hold to the “safe zone” his comic shops provide outside of the “vitriol” spread by all sides, and fears that politically explicit material may bring violence into his stores.

Though Boyle’s piece does present a popular view on comics’ function as a venue for escapism, I believe the history of four-color heroes shows that the escapism found in their stories has always been mixed with social commentary and political allegories. Even outside the stories themselves, the history of mainstream American comics can easily be read as one of exploitative businesses taking advantage of young creators. Marvel Entertainment itself, while employing many outspoken progressive writers like Mark Waid, G. Willow Wilson, and Nick Spencer, has as its CEO Ike Perlmutter, the billionaire financier who will serve as an advisor to Donald Trump on Veterans’ Affairs – a situation leading some to discuss the pros and cons of boycotting Marvel.

Such political actions by creators and publishers are nothing new. One prominent example of a comic book professional using his work to further a political agenda is Jack Schiff, a comic book writer and editor known for his work on Batman and Starman. Schiff was an outspoken progressive who was marginalized by DC publisher Jack Liebowitz and Superman editor extraordinaire Mort Weisinger, who referred to Schiff as “that crazy pinko.” (Weisinger, while extremely talented, was notoriously unpleasant to work with.) Schiff was in charge of the Batman books for many years, from the 40’s into the 60’s, and has become maligned in the history of comics as the man whose creative choices in the mid-50’s ran Batman into the ground. Super-villains were replaced by aliens, Batman gained a Bat-Family, and ridiculous stories – even for the time – became staple Batman fare. Some have suggested that this peculiar vision of the character was foisted upon Schiff by Weisinger and Leibowitz – perhaps in a misguided belief that what had revitalized Superman could do the same for Batman, or maybe to further cement Weisinger’s power at the company.

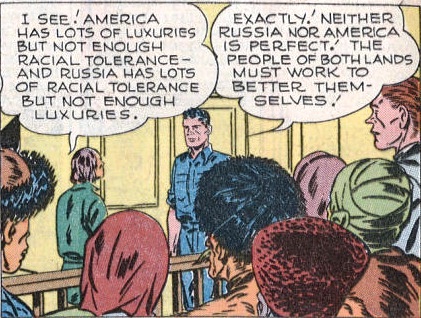

Schiff also wrote a backup feature with artist John Daly called “Johnny Everyman.” This unusual series featured its titular hero traveling the world to combat racism and promote peace. The character was conceived by the writer and political activist Pearl S. Buck as part of a co-venture between DC and the East and West Foundation, an organization she co-founded to encourage intercultural understanding. Throughout the mid-40’s, Johnny appeared nineteen times in World’s Finest and Comic Cavalcade, two titles featuring DC’s most popular superheroes. The series was not afraid to push the envelop, directly tackling anti-Black racism in the United States and even praising the Soviet Union for racial harmony. This was groundbreaking at a time when the norm for depicting Black and Asian characters was as racialized caricatures. “Johnny Everyman” did not sit well with some. This included popular newspaper columnist George Sokolsky, who penned an op-ed attacking “Johnny Everyman” titled “Liberals Subvert Comics.” How things change.

Jack Schiff’s greatest legacy to the comic community is a series of public service announcements, which appeared throughout the 50’s and 60’s in dozens of DC’s titles. Schiff wrote many (maybe even all) of the PSAs, which were sponsored by the National Social Welfare Assembly. These PSAs tackled a wide range of topics, but most tended to revolve around safety, education, or tolerance. By their very nature, PSAs are preachy, and Schiff’s are no exception. However, the best of them – especially those featuring Superman – remain affecting to this day. In these ads, we see Superman and other heroes earnestly appealing to America’s youth in an effort to combat bigotry, spreading messages relevant to our time in ads created over sixty years ago. This is why Martyn Pedler says that “superheroes have been social justice warriors all along.” That these images – though over half a century old – have gained new life on Twitter and comic book message boards is a testament to Jack Schiff’s commitment to using comic books to promote social justice.

It is often observed that superhero comics are, at their core, power fantasies – and perhaps that is true. But we should always remember who that fantasy is created for, and why. To do so we need only to turn to the words which first introduced Superman seventy-nine years ago in Action Comics #1: “Early, Clark decided he must turn his titanic strength into channels that would benefit mankind. And so was created…Superman! Champion of the oppressed, the physical marvel who has sworn to devote his existence to helping those in need!”