Racism was woven into our cultural fabric before we would even call ourselves the United States. It’s woven into the red, white, and blue of our beloved flag. From Uncle Tom’s Cabin to I Am Not Your Negro, we’ve made attempts in our art to apologize for and otherwise contend with our country’s past. It’s difficult to strike a balance in messaging. If you lean too sentimental, you miss the point. Too violent and you risk re-traumatizing those who experience racism daily and feel the ripples of slavery. Infidel from Image Comics manages to strike the balance.

In the midst of our new revolution and artistic efforts to help an American audience unlearn racism, my thoughts turned to this 2018 graphic novel. Written by Pornsak Pichetshote and illustrated by Aaron Campbell, I first read this a few months ago.

Alert: If you haven’t already read Infidel, here’s your SPOILER WARNING!

MFR ON YOUTUBE (latest video)

Help us reach 5K Subs!

A Familiar Story

Infidel is a horror graphic novel originally released as a five-issue series by Image. It’s the story of a young Muslim woman named Aisha who is being haunted by the racist ghosts of explosion victims on the top floor of her apartment complex.

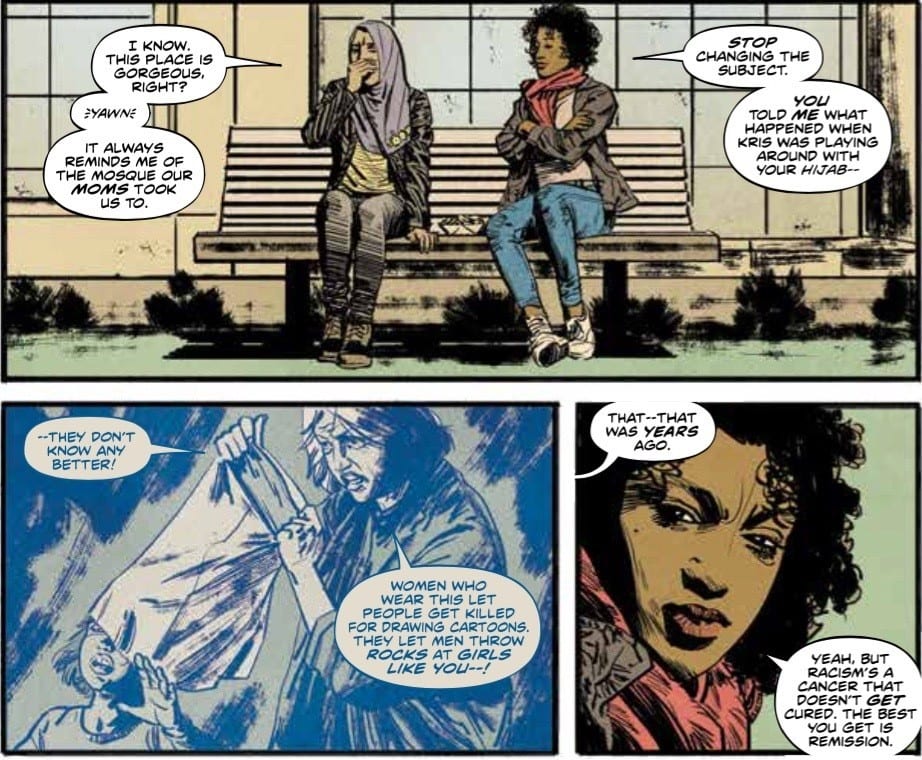

The haunting comes at a time when Aisha is dealing with tension between her white fiancé Tom and his mother Leslie, due to the older woman’s prejudice. Aisha is forgiving while Tom is not, putting her in an intermediary position and causing confusion for Tom’s young daughter, Kris. His bitterness and anger are shared by Aisha’s best friend Medina who, like Aisha, has lost her faith.

It turns out that this lack of faith is precisely what keeps Aisha around her fiancé’s family, and Medina’s story is ostensibly the same. Found family keeps these women alive. Tragically, the ghosts start to intensify these already strained relationships.

Despite an Atavan prescription, an investigation, and some exploration of the occult, nothing but another explosion can rid Aisha and her friends from these ghosts. Faith, a theme of the book, is also ineffective. Other than making a McGuffin out of Aisha’s misbaha (prayer beads), faith, like the occult elements, is weak in the face of the destructive power of racism, mental illness, and murder. As Medina says early in the book, “Racism’s a cancer that never gets cured. The best you get is remission.” Prescient words that resonate with current feelings of cynicism and weariness.

An Unlikely Choice

Medina embodies this cynicism and weariness, making her an unlikely choice of heroine. And yet she must avenge Aisha who becomes comatose after a ghost-involved accident which also causes the death of Leslie and serious injury to Kris.

Medina does her best to continue Aisha’s interrupted investigation. However, once she does find out the truth, her attempt at vanquishing the occult demons fails. The misbaha that could have exorcised the ghost breaks. Thus, Medina is forced to blow up the apartment complex, setting us back into the vicious cycle of racist blame.

The violence in this particular portion of the book is hard to witness given its roots in reality. Medina’s a martyr, but a villain to the press in the aftermath. We’ve read it before. Here, what keeps the reader invested is the empathy we now feel for these women. We want to scream at the reporters, “Medina was a person! She had no choice!”

I’d argue that the violence was necessary for such an emotional payoff. Medina couldn’t write her own story just like other victims of racial violence.

Reaching Out

In the aftermath of the explosion, Aisha wakes from her coma. She’s been declared innocent in the death of Leslie. Her new pastel world gets juxtaposed with a conversation between two white developers as they assess the ruins of Aisha’s apartment complex. They joke about the tragedy, and one tries to convince the other that people can change if you give them a chance. He says, “You just have to have faith” as the ghosts resurface behind them. It’s a self-aware sentiment reminding us that expressions of faith are tantamount to indifference in our harsh world.

What saves this from turning into a completely bleak ending is the image of Aisha reaching for her mother’s hand with Kris’s drawings making up the background. The message here being that cultivating strong bonds across divides can heal our broken society.

Infidel‘s creators, especially in the final chapters, balance the violent and avoid the sentimental except where it may serve a broader point. Their healthy cynicism gives the story nuance, appealing to the jaded reader. The creators want us to feel empathy and anger by the end. Anger toward racism, empathy for the victims of it, and perhaps, the urgency needed to enact social change.

A Familiar Hate

The book was indeed very timely when it came out in 2018, responding to a rise in Islamophobic hate crimes in the U. S. That was also the year in which President Trump’s “Muslim ban” saw its day in court. Regardless, Infidel doesn’t comment on these things directly. It’s never preachy, and it doesn’t rely on the ghosts to scare the reader. Rather, it poignantly delivers on the fear that racism both creates and is based upon.

One example of this can be found in a short scene in which Leslie, while riding the subway, clutches her purse tight to herself because she sees a Black man nearby. Campbell’s hard lines and attention to facial expressions turn a subtle moment into suspense. Actions like hers chill the bones of anyone capable of empathy.

We may not see the nationwide change our protests hope to achieve by the of the year. There were three years between the 1916 Rising and War of Independence in Ireland, and then another sixteen years before the country became firmly established with a constitution. It was two years between the Emancipation Proclamation and Juneteenth when every slave finally saw freedom. Racism can’t be eradicated, but social and political change will come.

Pichetshote never intended Infidel to be prescriptive. As Campbell said in an interview, “we didn’t seek to answer these questions as much as try to simply just ask the questions.” As such, it’s a good place to start to unlearn racism. You may pose the same questions asked in the book and have those difficult conversations. It may also move you to act.